Every Day is Earth Day

National Geographic Explorers are reshaping how we think about intelligent marine life. Join them as they inspire us to protect our ocean.

Using the power of science, exploration, education,

and storytelling to illuminate and protect

Investing in a diverse, global community of changemakers

Bold Explorers

We fund a global community of Explorers who investigate, test hypotheses, innovate, stretch their creativity, and push the boundaries of traditional thinking in ways that fundamentally change our world.

Impactful Programs

We support and cultivate a portfolio of diverse, Explorer-led programs within our five focus areas to drive impact and fulfill our mission of illuminating and protecting our world.

Connection & Education

We leverage our global expertise, platforms, and unparalleled convening power to inspire educators, youth, and future Explorers and help more people learn about, care for, and protect our world.

Responsible Stewardship

Our innovative business model allows us to invest every philanthropic dollar—100% of donations—directly to our Explorers and programs. Join us to support what matters most to you.

Mind the Water Gap

Maximizing impact

in five key areas

Revealing and protecting underwater worlds

Our Explorers discover, understand, and conserve marine and coastal systems and inspire and empower local and global audiences to better understand and protect the ocean.

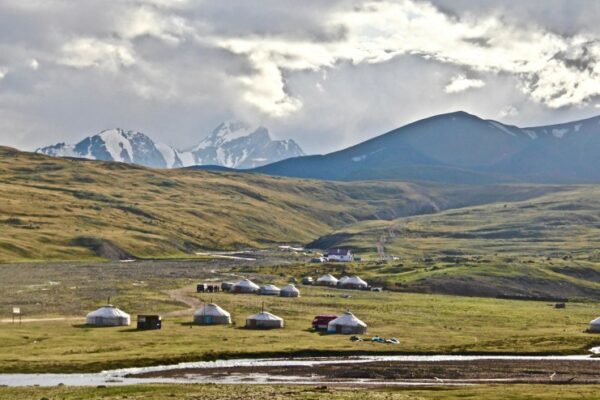

Preserving and protecting land environments

Our Explorers explore, understand, and conserve terrestrial and freshwater systems and inspire and empower local and global audiences to better understand and protect our lands, lakes, and rivers.

Protecting and conserving wildlife

Our Explorers inspire and empower local and global audiences to better understand and protect wildlife, including animals, plants and fungi.

Understanding our past and protecting our future

Our Explorers work to preserve cultural knowledge, better understand human histories, cultures, practices, diversity, and evolution—past and present, center communities, and inform and inspire global audiences with stories or lessons about humanity.

Supporting innovation

Our Explorers are taking novel and inventive approaches to address critical challenges and produce insights that illuminate and protect the wonder of our world.

Double Your Impact for Earth Month

Earth Day is April 22, but at the National Geographic Society, we are celebrating throughout the entire month of April. This Earth Month, you can join National Geographic Explorers as they illuminate some of nature’s most intelligent marine life and uncover the hidden wonders of our world. Donate during April, and your gift will be DOUBLED thanks to the support of generous donors. That means every dollar will go twice as far to protect the wonder of our planet.

Your impact begins today!

Supporting future changemakers

Co-founder of School of Leadership, Afghanistan (SOLA)

Meet Our Explorers

Meet Our Explorers

Our Funding Strategy

Our Funding Strategy

Cultivating an environment of opportunity, mutual respect,

and belonging

Learning from our past, examining our present, and building a more inclusive future.

We believe we can only achieve our mission to illuminate and protect the wonder of our world when people of every race, identity, experience, and ability have a role in our work. Although we have much more work to do, the Society has made strides to achieve and maintain equity.

Latest perspectives, news, and stories

Photo Credits (from top of page): Jason Gulley, Beverly Joubert, Sam Kittner, Joshua Irwandi, Chris Mbanza Schwagga, Manu San Felix, David Gill Below: Michael Nichols, Andy Mann, Paul Nicklen, Ami Vitale, Christian Tryon, Kenneth Garrett, Mark Thiessen