Volcanoes in history

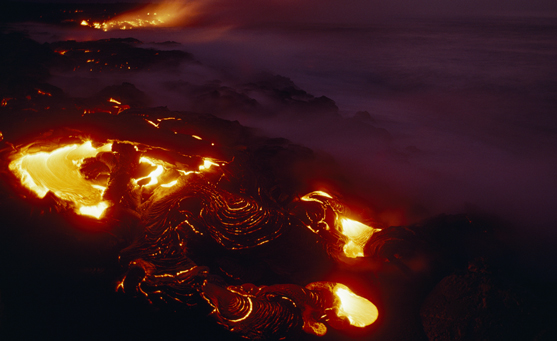

1. Kilauea, Hawaii

Type

Shield volcano with a cinder cone

Kilauea has been erupting almost constantly from its eastern rift zone since 1983. Finally in April 2018, the volcanic cone known as Puʻu ʻŌʻō (pronounced ‘po-oo-OH-oh’) stopped erupting as its crater floor collapsed. After 90 days or so of no activity, scientists could be confident its 35-year-long eruption had ended. While the eruption of Puʻu ʻŌʻō may be over, Kīlauea is still an active volcano and new eruptions are likely to happen in the future.

History of Kilauea

- Hawaiians believe Kilauea is the legendary ancient home of Pele, the Hawaiian volcano goddess.

- It emerged from the sea about 100,000 years ago and has been active ever since.

- It formed from an intraplate hot spot and is the most studied volcano in the world.

- Kilauea's constant lava eruptions have built up the volcano and given it a shield-like form that is still growing. Currently the shield is about 80 kilometers (50 miles) long and 24 kilometers (15 miles) wide.

Kilauea’s eruptions

- Kilauea’s eruptions are composed mostly of relatively gentle lava flows.

- It has erupted from three main areas: its summit and two rift zones.

- Lava fountains often shoot molten magma high in the air before it flows down the mountain's slopes. A spectacular lava fountain during a 1959 eruption from the Kilauea Iki vent soared 580 meters (1,900 feet), a record for a Hawaiian eruption.

Kilauea and earthquakes

On May 4, 2018, an earthquake with a magnitude of 6.9 struck Hawaii island. The earthquake's epicenter was near the south flank of Kīlauea. Most earthquakes that are directly beneath a volcano are caused by magma exerting pressure on the rocks until they crack.

Kilauea’s future

- In the future, scientists say Kilauea will continue its pattern of sporadic explosions causing some destruction but it will mostly give out gentle lava flows.

- Eruptions will fill the caldera and increase the height of the summit of the volcano.

2. MOUNT ETNA, ITALY

Type

Composite volcano with cinder cones, caldera

History of Mount Etna

- Mount Etna is on the island of Sicily and is the highest active volcano in Europe at almost 3,350 meters (11,000 feet).

- Mount Etna grew on the rift formed from the subduction of the African tectonic plate under the Eurasian tectonic plate.

- The oldest lava exposed on the lower flanks of the volcano issued from the depths of the Earth about 300,000 years ago.

- The philosopher Plato sailed from Greece in 387 BCE just to see the mountain.

- Ancient Romans thought it was the forge of their metalworking god, Vulcan.

Mount Etna’s eruptions

- Eruptions of Mount Etna were first documented in 1500 BCE. More than 200 eruptions have been recorded since then.

- Etna has erupted frequently, though the explosions are usually not large.

- The most dramatic explosion was in 1669, when 20,000 people were killed by an unstoppable wave of lava. Fissures opened on the volcano's sides, sending the lava flowing to the city walls of Catania. The lava rose to the top of the wall and swept over, destroying much of the town as well as a dozen other villages. Villagers tried to divert the fiery flow by digging a trench above Catania, but they were unsuccessful. A more recent attempt in 1983, in which scientists exploded dynamite to redirect the lava, was more successful.

Mount Etna’s future

- Mount Etna continues to belch debris and spew lava and has been increasingly active in the last 50 years.

- Recently fatalities have been rare as the volcano's outbursts occur higher up and its lava moves slowly giving people time to escape.

3. KRAKATAU, INDONESIA

Type

Composite volcano with caldera

History of Krakatau

- The 1883 explosion on an uninhabited island in Indonesia was one of the most catastrophic in history.

- Before the eruption, this island in the Sunda Straits between Java and Sumatra islands was made up of three stratovolcanoes that had grown together.

Krakatau’s eruptions

- In the summer of 1883, one of Krakatau's three cones became active. Sailors reported seeing clouds of ash rising from the island.

- The eruptions reached a peak in August, culminating in a series of tremendous explosions. The most ear-shattering eruption was heard in Australia, more than 3,200 kilometers (2,000 miles) away.

- The eruption sent ash 80 kilometers (50 miles) into the sky and blanketed an area of 800,000 square kilometers (300,000 square miles), plunging the area into darkness for two and a half days.

- The ash drifted around the globe, causing spectacular sunsets and halo effects around the moon and sun.

- The explosions also sent as much as 21 cubic kilometers (5 cubic miles) of rock fragments into the air.

Aftermath

- The northern two-thirds of the island collapsed under the sea into the newly vacated magma chamber. Much of the remaining island sank into a caldera about 6 kilometers (3.8 miles) across.

- The collapse set off an immense series of tsunamis, or giant sea waves, that traveled as far as Hawaii and South America. The largest wave loomed 37 meters (120 feet) high and destroyed 165 nearby settlements. All vegetation was stripped bare, structures were demolished, and some 30,000 people were washed out to sea in Java and Sumatra.

Future of Krakatau - Anak Krakatau

- Krakatau was quiet until the 1920s. In 1930, an eruption built a new cone, Anak Krakatau (child of Krakatau) in the center of the caldera created in 1883.

- Anak Krakatau has been growing and erupting since it formed in 1930—9.4 centimeters (3.7 inches) per week on average since the 1950s (4.9 meters (16 feet) per year).

- On December 22, 2018, an eruption caused a deadly tsunami, with waves up to five meters (16 feet) in height hitting nearby coastal areas. It is thought that one of the flanks of the volcano collapsed, triggering the tsunami.

- More than 400 people died and more than 40,000 were displaced.

4. VESUVIUS, ITALY

Type

Composite volcano

History of Vesuvius

A relatively young volcano, Vesuvius formed probably fewer than 200,000 years ago when the African and Eurasian plates collided in a subduction zone. The volcano was dormant for centuries.

Vesuvius’s eruption

- Vesuvius suddenly came alive on August 24, 79 CE.

- Scientists estimate that the eruption sent a column of ash 32 kilometers (20 miles) into the sky. The column then suddenly collapsed.

- Roughly three meters (ten feet) of tephra, or fragments of volcanic rock and lava, hit Pompeii. Everything was buried, except the roofs of some buildings.

- In the next stage of the eruption, a superhot river of steam and mud rushed down the volcano's slopes and into the seaside town of Herculaneum, traveling seven kilometers (four miles) in about four minutes.

- Victims there died so quickly from the intense heat—about 500°C (930°F)—that they did not even have time to raise their hands in self-defense, Italian archaeologists say.

- In just a few hours after it roared to life, Vesuvius's hot volcanic ash and dust had completely buried the Roman towns of Pompeii and Herculaneum. Their ruins were not discovered for more than 1,600 years.

- When archaeologists excavated the forgotten town of Pompeii, beginning in the 19th century, they found much of it preserved by the hot ash. By pouring plaster into the hollows left in the hardened ash by decomposed bodies, excavators made macabre body casts. The molds revealed the volcano's victims frozen at the instant of death.

Future of Vesuvius

Vesuvius last erupted in 1944. Today more than two million people live on and around Vesuvius. It is still considered a dangerous and potentially deadly volcano. The authorities offer to pay for people to move out of the eruption “red zone”.

5. MOUNT ST. HELENS, WASHINGTON, U.S.A.

Type

Composite volcano with lava dome

The eruption

On May 18, 1980, U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) scientist David Johnston was camping at an observation post near Mount St. Helens. From a base of operations in Vancouver, Washington, the USGS was monitoring the volcano, aware of the danger for a large eruption.

At 8:32 a.m., Johnston radioed the base: "Vancouver, Vancouver, this is it!"

The picturesque Cascade Range peak had erupted. The violent blast killed Johnston and 56 other people and tore off nearly 400 meters (1,300 feet) of the volcano's top. More than 600 square kilometers (230 square miles) of surrounding forest were devastated.

Volcanologists weren't surprised. The volcano, less than about 37,000 years old, had been especially active over the last 4,000 years. Eruptions, usually explosive, had occurred at a rate of about one every hundred years. Before 1980, the last eruption happened 130 years previously, and scientists were alert for the explosion.

A few months before the May eruption, a series of earthquakes began to shake the volcano. Several small steam eruptions occurred, new fissures appeared, and a bulge developed on the north flank of the volcano.

The bulge got larger and larger. A week before the big eruption, it was expanding at a rate of about two meters (seven feet) per day.

When the big blast occurred, the entire northern slope of the volcano above the bulge slid downward. The huge landslide sparked a hydrothermal blast that swept through the surrounding forests, snapping trees like twigs.

In addition, a column of volcanic rock and lava fragments rose from the volcano's summit to a height of 20 kilometers (12 miles). The eruption lasted nine hours and spread debris as far as the Great Plains.

The eruption destroyed the volcano's peak, replacing it with a horseshoe-shaped crater. Since the 1980 blast smaller eruptions have built a lava dome over the vent.

Future of Mount St. Helens

Between 2004 and 2005 Mount St. Helens gave out steam and ash. Until 2008 it continuously gave out three years of semi-solid lava. It is likely that Mount St. Helens will erupt again. However, an eruption like the one in 1980 is unlikely now that a deep crater has formed.

6. SOUFRIERE HILLS, MONTSERRAT

Type

Composite volcano with lava domes

History of Soufriere Hills

Underneath Montserrat, the North and South American plates push beneath the Caribbean plate in a subduction zone. From this tectonic activity rose Soufriere Hills, a stratovolcano on the southern end of the island.

The eruption

- The volcano had been quiet for nearly 400 years until 1995, when it burbled to life and sent islanders scurrying.

- A series of eruptions began with occasional gray clouds of ash and steam. Then came pyroclastic flows—destructive mixtures of extremely hot volcanic fragments and gases that sweep along close to the ground. The flows swept down the volcano's eastern side and turned a green valley into a brown moonscape.

- In September 1996, part of the volcano's dome collapsed, sending rocks shooting out of its crater for nearly an hour. The stony debris pelted nearby residents.

- The government, fearing casualties or deaths, evacuated the southern end of the island, prohibiting anyone from inhabiting homes or businesses there. Evacuees fled to the north, jamming churches, community centers, and other makeshift shelters. Eventually more than half the population left the island, many taking advantage of free aid from Britain.

- In 1997, an eruption killed 19 people and buried the evacuated capital, Plymouth, under a thick layer of ash and mud. It became a ghost town, with most people leaving the island.

Soufriere Hills future

Soufriere Hills continues to throw ash and stone periodically across the southern part of the island.